In this timely and important book, philosopher Susan Neiman explores how we can ethically and constructively address past historical wrongs. She does this by combining philosophical reflection with personal stories and interviews with Germans and Americans who are actively engaged in the work of vergangenheitsaufarbeitung, a German word which literally means working-off-the-past. She brings depth and compassion to the issues, drawing from her own intimate connections to the US and Germany, shaped by her life as a white girl in the segregated South and later years working and raising her children as a Jewish woman in Berlin.

In thinking about the immense evil of Nazism, the author is guided by Bulgarian-French critic Tzvetan Todorov’s injunction: “Germans should talk about the singularity of the Holocaust, Jews (and all non-Germans) should talk about its universality.” For the most part, she argues that many Germans have embraced this idea and view attempts to compare the Holocaust to other evils as efforts at denial. As she recalls, nearly every German she knew laughed out loud when they heard she was writing a book about what others can learn from Germany’s efforts to deal with their Nazi past; the only exception being a former culture minister who raising his voice said that under no circumstance should she publish such a book.

But for many other peoples, the image of the Holocaust as the incarnation of evil has served to support the denial of their own historical wrongs. This is certainly true of the United States and its racist past; while Hitler found support for Nazi policies in the United States’ treatment of its black population, for most Americans, the idea of the Holocaust as the ultimate definition of evil works to silence serious thinking about their country’s past wrongs. Neiman draws out the significance of the Washington Mall having a Holocaust museum but no monument remembering American slavery. Neiman asks: “Would we object to Germans who acknowledged that the Holocaust was terrible – but built a monument commemorating American slavery in the center of Berlin?”

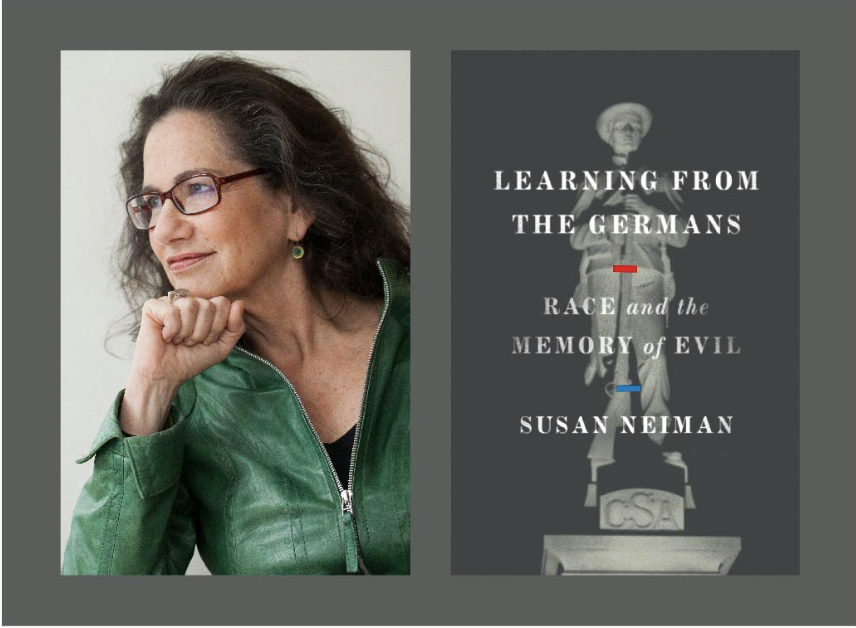

African American lawyer Bryan Stevenson, who led the initiative to create the new National Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, says that what is lacking is any sense of national shame. Neiman adds that modern Southerners agree that slavery was wrong, but there is a blank to everything that followed, including the Jim Crow laws and the lynchings of thousands of black people. Then there are the multitude of Civil War statues across the South erected during two distinct periods — some 50 years after the end of the Civil War and in the early 1960s — in an intentional effort to rewrite history and reinforce white strength at a time where black Americans were seen as gaining power.

While Neiman urges us to learn from the Germans, she stresses that the process has been a difficult one. In the first few decades after WWII, most Germans were obsessed with their own suffering and in a state of denial about Nazi atrocities. It was not until the mid-1990s that the final taboo in West Germany, that Nazi crimes were not limited to the elite SS forces but also involved the active participation of ordinary soldiers from the German army, was broken with the opening of the Wehrmacht photo exhibit. While Germany today is facing a renewed threat from the new right and neo-Nazis, Neiman finds hope in the responses of so many other ordinary Germans. Four thousand white nationalists rioting in Chemnitz, about a year after Charlottesville, made front pages around the world, but less noticed were the quarter of a million people marching soon after in the streets of Berlin to condemn right-wing racism. Even in 2018, far more Germans were actively engaged in supporting refugees than voting for right-wing parties.

As educators, there is much to learn from this informative, moving and hopeful book. The interviews with Germans and Americans working to foster the acknowledgment of difficult truths remind us of the value of nonviolence, respectful dialogue and storytelling to open up conversations. As Neiman examines some of the criticisms of the German approach to working off the past, I found interesting connections to the pedagogy of this project, and a shared understanding that changing deeply rooted, harmful ideas and values is a difficult process that needs to be well-conceived. Some involved in working to confront the current climate in Germany where overt racism has become more permissible are critical that past efforts have focused excessively on the suffering of victims, failing to providing sufficient understanding of how the Holocaust happened, or draw more general lessons about prejudice, persecution and genocide and engaged people to think about the possibility of resistance, even in the darkest of times. These criticisms point to a multi-faceted approach that seeks to develop critical thinking, empathy for human suffering, and a sense of agency – all central to the Resist Violence pedagogy.

Awesome post! Keep up the great work! 🙂